Pushkin’s Attend Exclusive Bonhams & Office of Tibet Event on the 14th Dalai Lama

Pushkin’s was recently honoured with an invitation to an exclusive evening hosted by Bonhams in partnership with The Office of Tibet. The occasion centred on a lecture and reception titled ‘The Divination, Search & Installation of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama’, held at Bonhams, New Bond Street, on Monday 2nd June.

Guests were treated to a compelling lecture delivered by Alexander Norman, acclaimed biographer and author of The Dalai Lama: An Extraordinary Life. His insights provided a deeper understanding of the remarkable and little-known process behind the recognition and enthronement of the young Tenzin Gyatso as the 14th Dalai Lama.

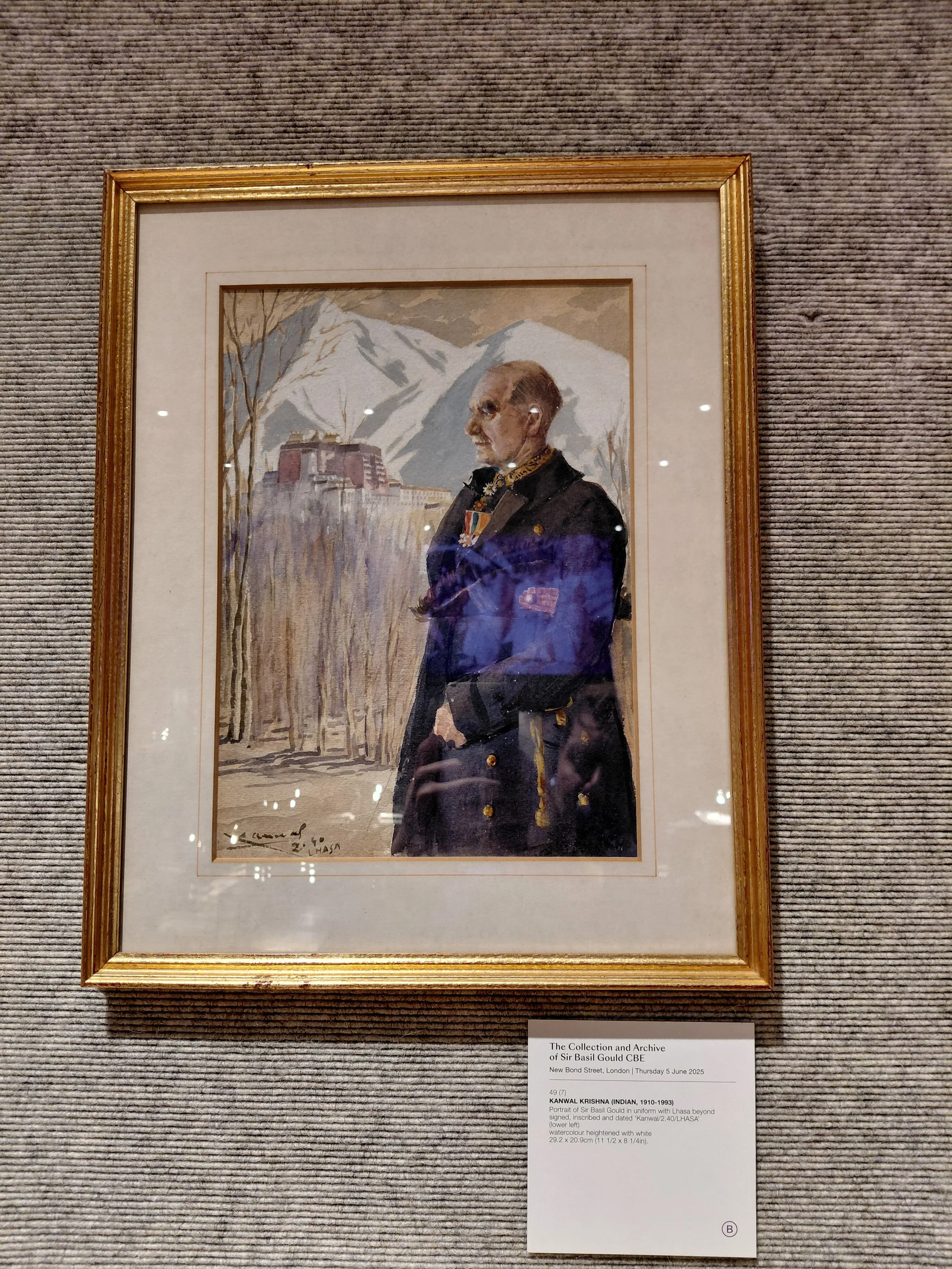

Adding to the significance of the evening was a preview of a group of rare paintings by Kanwal Krishna, which form part of the forthcoming auction The Collection and Archive of Sir Basil Gould CBE. These evocative works capture key moments and rituals associated with the Dalai Lama’s discovery and early life, offering both artistic and historical value.

It was a privilege for Pushkin’s to attend such a remarkable event, which brought together scholarship, history, and fine art in a setting befitting the subject matter.

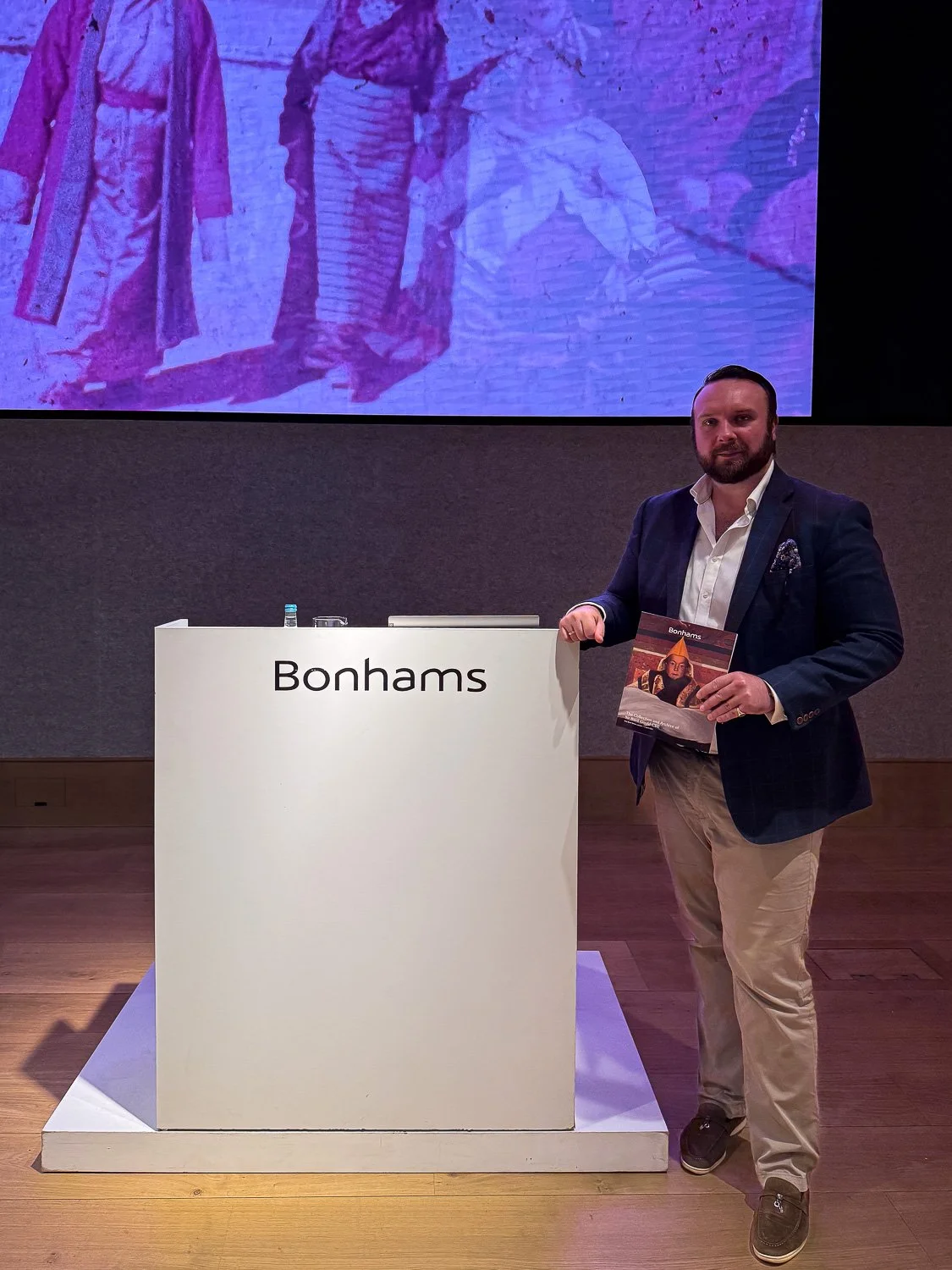

Mr Pushkin himself attending the event

(A portrait of Sir Basil Gould in Uniform by Kanwal Krishna)

Sir Basil Gould and Tibet: A Diplomatic Chapter in the Eastern Himalayas

Sir Basil Gould CBE, CIE (1883–1956), was a British diplomat whose involvement with Tibet left a lasting imprint on Anglo-Tibetan relations during the first half of the 20th century. As the British Political Officer for Sikkim, Bhutan, and Tibet from 1935 to 1945, Gould undertook several key missions to Tibet, including in 1936 and 1940, where he engaged directly with Tibetan leaders – notably the young 14th Dalai Lama.

Gould’s connection to Tibet began much earlier. In 1912, he was appointed British Trade Agent in Gyantse. At that time, the 13th Dalai Lama was seeking to modernise Tibet, and one of his initiatives involved sending four Tibetan boys to England for their education. Known later as “The Rugby Boys”, these students were enrolled at Rugby School in 1913, with arrangements handled by Gould himself. This marked an early cultural exchange between Tibet and the West. That same year, Gould accompanied the 13th Dalai Lama on his return journey to Tibet.

In August 1936, Gould led a British diplomatic mission to Lhasa. The aims were twofold: to discuss the possible return of the 9th Panchen Lama, and to explore military aid. Although the Tibetan authorities were hesitant to approve a permanent British presence in Lhasa, Gould's efforts bore fruit. His delegation included Hugh Richardson, who remained in Lhasa as a commercial representative and maintained regular communication with British India by radio.

The defining moment of Gould’s diplomatic career came in early 1940, when he attended the enthronement of the 14th Dalai Lama. For this, he was later knighted. Demonstrating notable foresight, he commissioned the Indian artist Kanwal Krishna to document the ceremony and its principal figures. Though operating in different realms – diplomacy and art – both Gould and Krishna shared a deep engagement with Tibet. Their respective work offered complementary insights: Gould through his political and historical records, Krishna through his visual interpretations. Together, their contributions enriched contemporary understanding of Tibetan society at a time of major upheaval.

(Artwork by Kanwal Krishna from the Ceremony)

Despite the Second World War casting a long shadow over British influence abroad, during the 1930s Tibet still regarded Britain as a potential counterbalance to growing Chinese pressure. Following the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, the Great Thirteenth Dalai Lama had declared Tibet independent. Yet it was well recognised that Tibet’s ability to maintain autonomy rested on the support of a powerful ally – and without it, Chinese ambitions over the region would likely be renewed.

Britain, however, proved hesitant. The 13th Dalai Lama’s offers of friendly ties were met with little more than polite deflection. His hopes for British backing in his efforts to formalise Tibetan independence were left unfulfilled, and the limited arms supplies provided to his new standing army were inadequate. Seeking alternatives, he attempted to build relations with Tsarist Russia – only to discover that the Soviet regime’s stance on religion made it a dangerous and ultimately unsuitable ally.

Against this backdrop, the enthronement of the 14th Dalai Lama presented a rare opportunity to reinforce ties with Britain. The hope was that the new Dalai Lama’s advisors would recognise the importance of unity during his minority and after his accession to full power. But beneath the surface, a deeper struggle was already beginning.

Sir Basil Gould’s presence in Lhasa in 1940 coincided with the initial signs of a spiritual conflict – a power struggle centred on the Dalai Lama himself. This internal rift would, in time, come to threaten not only his own position but Tibet’s continued existence as an independent state. His mission, therefore, took place at a pivotal moment, with long-term consequences both politically and spiritually.

The Gould Expedition, 1939–40: A Mission Amidst Intrigue

By the time of Sir Basil Gould’s final expedition to Tibet in 1939–40, tensions were already beginning to emerge behind the ceremonial splendour of the Dalai Lama’s enthronement. Just weeks before the young hierarch was formally installed, a significant political shift occurred: the charismatic Reting Rinpoché was removed as Regent and replaced by the more conservative Taktra Rinpoché.

(Portrait of Reting Rinpoché, painted by Kanwal Krishna)

The origins and implications of the Reting affair are too complex to detail here. But it is enough to note that from the very outset of his leadership, the Dalai Lama found himself at the centre of a web of political and spiritual power struggles. His ability to navigate these threats over the decades speaks volumes about his exceptional leadership – in both religious and secular domains.

From Kanwal Krishna’s remarkably intimate portraits of Tibetan dignitaries, we catch a rare glimpse of the atmosphere that surrounded the Dalai Lama’s early years – and of the extraordinary circumstances that shaped his rise. The backgrounds of key figures captured in Krishna’s work offer important context to the precarious state of Tibetan politics during this period – a situation foreign dignitaries such as Gould could only observe from the periphery, likely unaware of the full extent of what was unfolding.

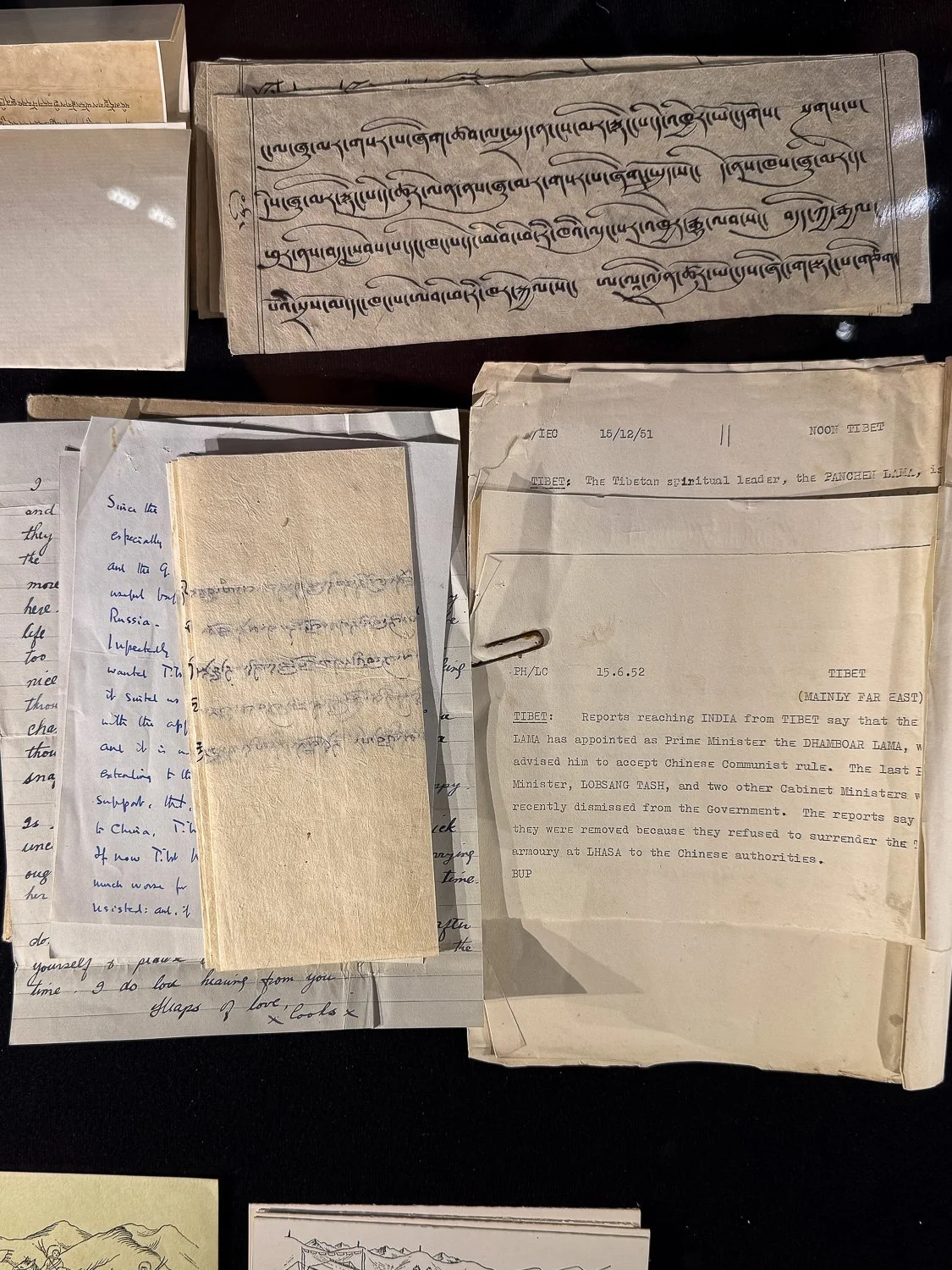

(A photograph from the “Lhasa mission diary”)

During the course of Gould’s mission, a weekly Diary of Events was compiled and submitted to the British Government in both India and London. The first entry was filed from Karponang, Sikkim on 31st July 1936, and the final report marked the Mission’s departure from Lhasa on 17th February 1937. These diaries were accompanied by a carefully curated selection of photographs drawn from working albums, which served as drafts for the final submissions.

Frederick Spencer Chapman, Gould’s private secretary, later recalled in his memoirs that the Mission “kept a general diary accompanied by photographs, which was sent off each week to the Government of India.” Three individuals were responsible for authoring these diary entries: Spencer Chapman himself, along with Philip Neame and Hugh Richardson.

The photographs included in the diaries were developed and printed at the Mission house in Lhasa – the Dekyi Lingka – using negatives taken by Spencer Chapman and other team members. These were then mounted into albums made of locally sourced Tibetan paper.

Chapman noted in his memoir that he undertook all of his own photographic developing. “The Lhasa water,” he wrote, “was suitable for this if strained through a handkerchief.” It was a process both resourceful and reflective of the Mission’s unusual setting – and its delicate balancing act between formal diplomacy and day-to-day improvisation.

The 1936–37 Gould Mission would go on to be recognised as one of the lengthiest and most productive British visits to Lhasa. Among its most notable achievements was the vast photographic record it produced – a visual account that became a defining element of the Mission’s success. Indeed, the use of photography as a key component of official reportage within the Diary of Events marked a turning point in how British missions documented and represented their presence in Tibet.

(Documented information, previously “Classified”)

(Kanwal Krishna’s portrait of the Dalai Lama)

The albums themselves were compiled using Daphne paper, also known as Lokta paper, a traditional Himalayan material made from the bark of the Daphne bush. This gave the diaries a uniquely Tibetan character, anchoring their content in the very landscape they were created to reflect.

A Royal Audience and a Lasting Impression

In early March 1940, Kanwal Krishna completed a remarkable portrait in oils. The subject was the newly enthroned Dalai Lama, painted from life in Lhasa. The portrait captured the boy as he appeared to the British Mission during an official audience held on 13th February, just before the formal enthronement ceremony.

Sir Basil Gould, who led the Mission, described the encounter in his memoirs. “February 13th was fixed for the reception of the British Mission by the Dalai Lama at the Norbhu Lingka,” he recalled. “The Hall in which the Dalai Lama grants audiences is a simple room of moderate size, lighted from a central square shaft supported on painted pillars. The courtyard outside was thronged with monks on duty and other monks who had come to receive a blessing.”

Upon entering the room, the British delegation saw a striking figure seated high on a simple throne: “a solid solemn but very wide awake boy, red cheeked and closely shorn, wrapped warm in the maroon-red robes of a monk and in outer coverings, cross-legged in the attitude of Buddha.” In turn, each member of the Mission approached. Gould presented the traditional white silk scarf; a scarf blessed by the Dalai Lama was then placed around his neck. “Two small, cool, firm hands were laid steadily on my head,” he noted. “And so the audience ended. The Dalai Lama was lifted down from his throne by the Chikyab Khenpo and left the Hall of Audience holding the hands of two Abbots.”

Artist Kanwal Krishna was also present and later recounted the unforgettable moment their eyes met. “The first time that I saw the Dalai Lama was when the British went to him for a blessing,” he said. “His eyes met my eyes... A peculiar thrill went through me.”

A few days after the enthronement, a children’s party was held at Dekyi Lingka, the British Mission’s residence in Lhasa. It was here that the portrait first drew notice. Gould remembered the moment clearly: “Among the first to arrive was the family of the Dalai Lama. Kanwal Krishna had recently finished a half-length portrait of the Dalai Lama in oils. The eight-year-old brother monk noticed it immediately and, if he is always as openly affectionate to the Dalai Lama as he was to the picture, he must be very fond of him indeed.”

The Dalai Lama, born in Amdo province and given the name Lhamo Thondup, was identified as a child of special destiny from an early age. Around the age of eighteen months, he was presented to the 9th Panchen Lama, and by the time he was four, he had passed a series of tests and divinations which confirmed him as the true reincarnation of the Great Thirteenth Dalai Lama, who had died in 1933.

Since his enthronement in 1940, few who have encountered him have doubted that they were in the presence of someone exceptional.

(A painting of the Dalai Lama arriving in Lhasa by Kanwal Krishna)

His greatest achievements span both the political and spiritual realms. In the temporal sphere, he has succeeded in bringing cohesion to the often fragmented world of Tibetan politics. By the 21st century, Tibetans are more united under his guidance than they have been since the 7th century.

Spiritually, his global impact has been profound. Largely through his efforts, Tibetan Buddhism has gained widespread recognition beyond the Himalayas, establishing centres throughout the West. The modern popularity of mindfulness and meditation, rooted in Buddhist teachings, owes much to his influence.

But beyond his accomplishments lies the man himself – someone who embodies the values he teaches: modesty, compassion, humility, and perseverance. He is known to take seriously the idea of placing others before oneself, and for treating even his adversaries as valuable teachers. Unlike many religious figures, he does not merely preach; he lives his philosophy – quietly, persistently, and with unwavering purpose.

A great man, if ever there was one.

Kanwal Krishna: Artist at the Coronation of the 14th Dalai Lama

In 1940, amidst the sweeping political changes across British India, a remarkable event unfolded high on the Tibetan plateau: the official recognition and enthronement of a two-year-old boy as the 14th Dalai Lama, spiritual leader of Tibet. While this episode is steeped in religious and cultural tradition, it is through the eyes of Indian artist Kanwal Krishna and his wife, fellow artist Devayani, that we gain a vivid, human perspective of this historic moment.

(A photograph of Kanwal Krishna)

Kanwal Krishna, a graduate of the Government College of Art & Craft in Calcutta, was not simply a painter but a chronicler of India’s spiritual and cultural dimensions. His artistic journey took him across India, and in 1940 he and Devayani ventured into Tibet. Their timing was serendipitous. They arrived just as preparations were underway in Lhasa for the official enthronement of Lhamo Dhondup—the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama—as the 14th Dalai Lama.

Tibet had located the child in 1937, and he was brought to Lhasa in 1939. The formal enthronement took place at the Potala Palace in 1940. This moment was not only a key turning point for Tibet but a rare opportunity for outside observers. Foreigners were seldom granted access to such deeply sacred ceremonies, yet the Krishnas, by virtue of timing and mutual respect, were invited to witness and document the occasion.

For Kanwal Krishna, it was not merely a religious rite he was witnessing, but a convergence of centuries-old spiritual lineage and the delicate political balancing act Tibet performed with its powerful neighbours—British India and China. His sketches and paintings from this period reflect more than ceremony; they capture the atmosphere, the gravity, and the emotional resonance of a culture in transition.

(A selection of Kanwal Krishna’s paintings from Tibet)

(A selection of Kanwal Krishna’s paintings from Tibet)

This experience profoundly shaped his work. Upon returning to India, Kanwal Krishna continued to exhibit widely, with shows in London, Paris, and across India. He remained committed to portraying the spiritual life of the Indian subcontinent and the wider region, bridging art and ethnography. The Dalai Lama’s enthronement became a key thread in his tapestry of cultural documentation.

Today, as we reflect on the legacy of both the 14th Dalai Lama and the artists who bore witness to his rise, Kanwal Krishna’s work remains a testament to the power of art to preserve moments that might otherwise have been lost to history. Through his brush, the distant rituals of Lhasa live on.

The event at Bonhams offered a rare and moving convergence of history, art, and diplomacy, shedding new light on one of the 20th century’s most significant spiritual transitions. For Pushkin’s, it was not only an honour to attend but a reminder of the vital role cultural institutions can play in preserving stories that might otherwise fade from view. Through Alexander Norman’s lecture, Kanwal Krishna’s paintings, and the legacy of Sir Basil Gould, guests were afforded a deeply human glimpse into Tibet’s past, a moment in time when faith, politics, and identity intertwined. It is a history that still resonates today, and one that continues to inform our understanding of Tibet’s place in the modern world.